a case for scribbling in your books

And for dog-earing them, and inscribing them, for reading them in pools and wiping dirt on their pages and letting them get battered to death in your purse

Lately: I made the blondies from Nancy Silverton’s new-ish cookbook, “The Cookie That Changed My Life,” and they came pretty close to unseating Ina Garten’s brownies as the best bar cookies I’ve ever consumed. I’m really excited to keep baking my way through Silverton’s sweets. … I went to a friend’s for dinner this week, and she made this salmon, and it was delightful. … I submitted a piece of short fiction I wrote to a couple literary journals, which feels like a good step toward my general goal of writing more fiction than nonfiction. I’m curious to see how the process plays out, and when everyone ends up rejecting the story, I’ll just publish it here instead.

a case for scribbling in (and dog-earing, and inscribing) your books, for reading them in pools and wiping dirt on their pages and letting them get battered to death in your purse

A few weeks ago, somewhere in the air over New England, I was using an hour-long, internet-free flight as an excuse to read a library book uninterrupted. It was a hardcover, plastic-sheathed and crisp, without so much as a single dog-eared page corner. This was a book that didn’t yet know how to be read, its pages determined to flip-flip-flip in sequence, its spine unwilling to yield.

I wondered if I was the first person to check it out. I silently cursed when I lay it, open, on my tray table for the amount of time it took me to scratch my nose and wound up losing my place instantaneously. And then, at the end of a chapter, I turned a page and found a single, short, dark hair wedged into the crease. My first thought: Look, a sign of life!

Someone had been there before me and left a bit of himself, and if I were nominally less sentimental about books and the act of reading, I might’ve been grossed out. Instead, I felt a connection. This brown-haired stranger read the book, and I was reading the book, and maybe I too would leave some sliver of myself behind. The next person might do the same, and eventually the book would learn how to be, how to sit open and hold its place and tell its story even more smoothly than this first, second, third time.

***

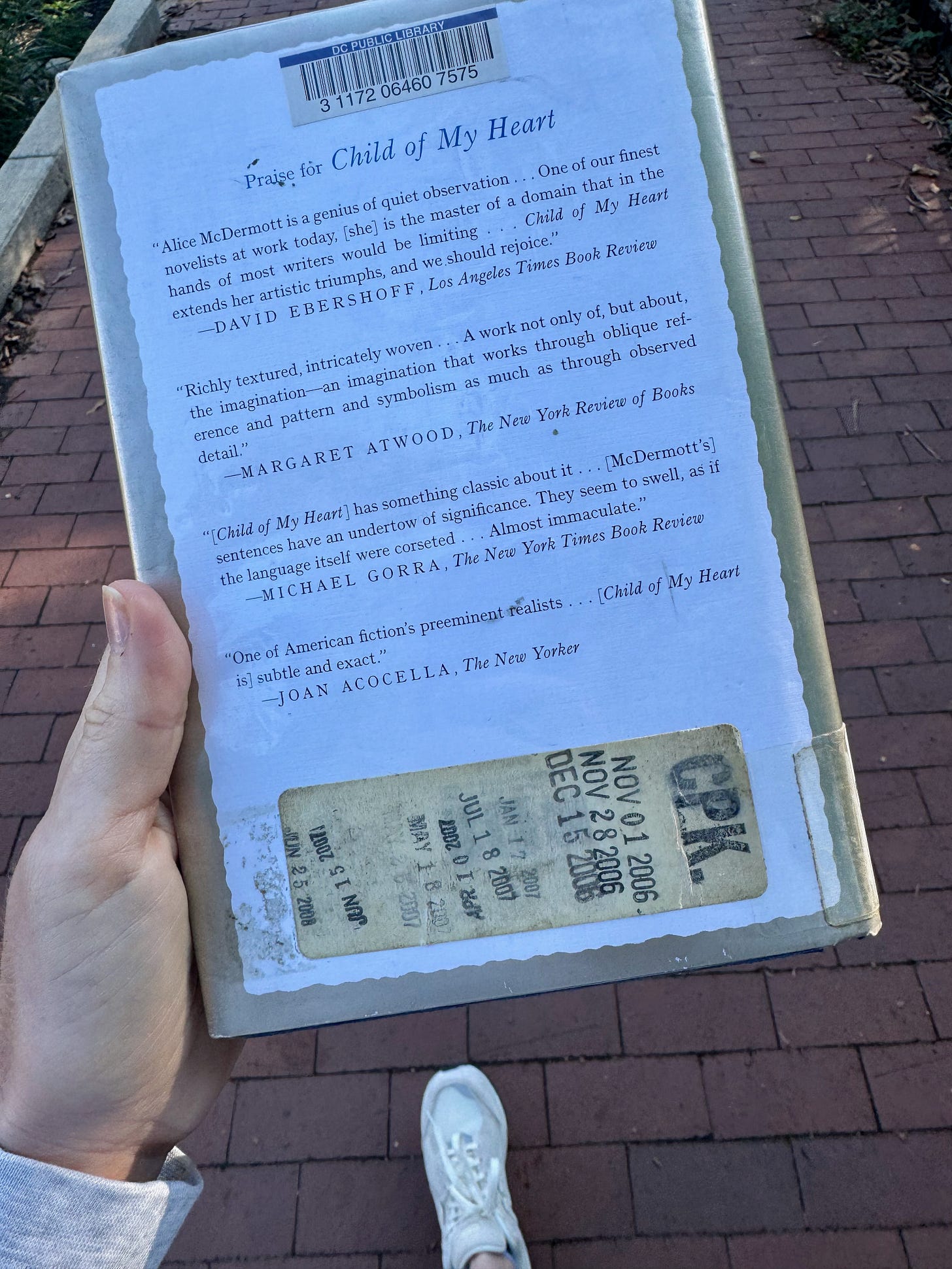

Feet on sidewalk, a different library book in hand, I felt myself subconsciously fiddling with a tear in the plastic cover. This book was old, I realized as I walked toward home, published in 2006 and looking even more weathered than its 18 years. On the back cover, a sequence of date due stamps were tattooed vertically: NOV 1, 2006, NOV 28, 2006 — a new marker every three weeks or so, through mid-June, then nothing for a year, then one final stamp. And so I wondered: Why ink up the book itself, not a card? And what happened after June 2008? Is that when the D.C. Public Library gave up stamps for good?

In my hand was a book that had entered the library’s circulation a few weeks after I moved into my freshman dorm at Georgetown. The second time it was checked out, it was due the night before my 19th birthday, and looking at that indelible stamp, I pictured the outfit I’d worn to celebrate: a stiff, short black skirt and a white tee, a red barrette in my hair. I remembered an old D.C. taxi, with its map of zones, dropping my friends and me off at a dark Moroccan restaurant on New York Avenue, with plush couches and belly dancers and steaming bowls of saffron rice.

There’s a Solidcore Pilates studio there now, and a PWC accounting office upstairs, and I wouldn’t be caught dead in a skirt so short, but this little book about a Catholic family on Long Island in the middle of the Vietnam War survived and told me its story, and now it’s back on a shelf for someone else to find. I wished, when I dropped it in the return bin, that I could add another stamp.

***

I read Sloane Crosley’s first essay collection while floating on a raft in my parents’ pool, which is now a flat expanse of grass. The book’s edges got wet and wound up rigid and crimped, and I have no idea what happened to it as the years wore on. I do know that I gulped down Crosley’s prose and thought desperately of the things I’d do to write that well, with that much wit.

I kept reading her essays whenever I found them, in Esquire and GQ, the New York Times and the New Yorker. I checked her books out of the library and unsuccessfully combed the Internet for her email address and stopped myself from requesting to follow her private Instagram account. You admire this woman’s career, I reminded myself. No need to mail her a lock of your hair.

As a preteen, I was repeatedly baffled by my friends’ celebrity crushes. I feigned excitement as they wrote cards to Justin Timberlake and mailed mixtapes to Nick Carter, struggling to stop myself from blurting out what I was thinking. I viscerally recall that queasy discomfort now whenever I think about my favorite authors, about Crosley and Ann Patchett and Joan Didion and Alice McDermott, these women whose writerly auras I would do anything to bask in. And so this week, when my husband and I arrived at the Kennedy Center to hear Crosley speak, I decided not to buy a copy of her most recent book, which was for sale at the entrance. I’d gotten it from the library and loved it and returned it, and I was there to listen, not to fawn.

At the end of the talk, my husband turned to me. “Are you sure you don’t want to try to get a book signed?” I was not sure. I wanted to, badly. So we raced to the table, where a few copies remained. I tapped my credit card too aggressively and the machine gave an ugly squawk, but on the second try, the copy was mine. Then I was in line, and it moved slowly, which meant Crosley was talking to each person, which prompted me to sulk and whine. “What am I supposed to say?” My husband rattled off a long list of potential topics: I could mention the recent New Yorker essay she wrote about her cat. I could tell her which of her books is my favorite. I could share that I’m a writer. (Absolutely not.) In the end, I stood in front of Sloane Crosley and handed over my copy and smiled, and she was lovely. “I’ve been such a huge fan since ‘I Was Told There’d Be Cake,’” I blurted out, too fast. She apologized for her bad handwriting and wrote a barely legible note, thanking me for reading her work for so many years.

It was written in heavy black ink, and I rejoiced at the imperfection of her squiggly letters. Who else will read that note someday? Will they be able to make out her message? I see it, and I smell chlorine.

***

Years ago, I went to an estate sale at an NBA player’s house, thinking I might write a story. I’d heard it was a bizarre scene, tchotchkes everywhere, strange stains on carpets, furniture that barely fit the rooms. The rumors were true; the number of salt shakers was staggering. The entire mansion looked like the set of a community theater play; touch anything, and it’ll topple over, a two-dimensional trick. In an office with floor-to-ceiling built-ins, I approached a few shelves of books, and when I tried to pull one out, an entire row followed. They were trick books, glorified cardboard boxes, like AI decor brought to life. I pushed the box-books back where they’d come from quickly, flinching as if I’d been burned.

It was a good reminder: Books aren’t decor. Sure, my house is full of them — I’m guessing 800 in 1,800 square feet — and they’re central to the way the space looks and feels. But they are books to be read, and they have more in common with the couch than they do with a vase or picture frame. And just as my couch’s cushions are dented, with a few tiny snags, so too should a book be imperfect. It should be stamped or inscribed, its pages molded by a dozen different grimy fingerprints, its best passages circled in pen. I’ve been doing that more lately to the books I own — an underline, a star, the outline of an exclamation mark in ballpoint pen1 — because why not? Half the fun of reading is remembering the story of where you read, and when, and why you felt the things you felt. Shelve them when you’ve finished, and loan them out, and donate them when the time comes. Mess them up, and give them another story to tell.

Unless, of course, they’re library books. In that case, please do respect them, even if you bemoan the extinction of date due cards and stamps.

This was my favorite column yet!